Kosicki v Toronto (City)

2023 ONCA 450 (CanLII)

Sossin J.A. – #

Overview #

Can private landowners gain title over municipal parkland through adverse possession? This is the central question raised on this appeal. The application judge answered this question by finding that municipal parkland is immune to adverse possession. While I would not accept such an immunity arises at common law, I conclude the application judge was correct in finding that the municipal parkland at issue in this case was not available for adverse possession. For the reasons that follow, I would dismiss the appeal.

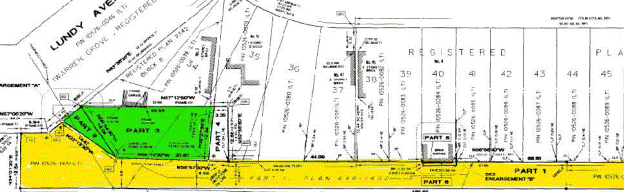

The appellants own a property near the Humber River on the southeast corner of Lundy Avenue and Warren Crescent. There are 26 other residential properties east of the appellants' property. The City of Toronto is the registered owner of a strip of land on the south side of these properties (the “City Lands”). For simplicity, the City Lands can be described as comprising three sections (as represented on the diagram below): i) a laneway that runs along the southern boundary of the properties and which has been used for over 40 years to access the rear-facing garages of the residential properties on Warren Crescent (Part 1 in the diagram below); ii) a trapezoid-like parcel of land behind the appellants' single-family house, which has been fenced and used exclusively by the owners of the appellants' property since at least 1971 (the “Disputed Land” identified as Parts 2 and 3 in the diagram below); and iii) a rectangular parcel of land, which the City consented to transfer to the appellants' easterly neighbour (Part 4 in the diagram below).

The City Lands are adjacent to Étienne Brûlé Park, a park that runs along a section of the Humber River. The City’s Official Plan designates this park and the Disputed Land as part of the City’s “Green Space System”. According to the City, the Green Space System is comprised of those lands that are large and have significant natural heritage or recreational value. In particular, within this system, the Disputed Land is designated as “Parks and Open Space Areas”, intended to provide public parks and recreational opportunities. It is official City policy to discourage the sale and disposal of lands in the Green Space System, such as the Disputed Land.

Sometime between 1958 and 1971, a fence was erected by the then-owners of the appellants' property around the Disputed Land, enclosing it within the backyard of the appellants' house. The public has not been able to access the Disputed Land since at least this time.

The appellants use the Disputed Land as a play area for their children and maintain it as part of their backyard. The appellants have paid realty taxes on the Disputed Land, and the City accepted those payments until 2020. The appellants approached the City about purchasing the disputed lands in 2021. The City, based on its policy, refused to sell, so the appellants brought a claim for adverse possession.

Decision Below #

The application judge found the appellants' claim would have met the threshold for adverse possession, as the Disputed Land was fenced in by the previous owners of the property since at least 1971, with no objection from the City. The previous owners of the appellants' property, as well as the appellants, have maintained undisrupted and exclusive possession of the Disputed Land.

While the facts at hand would have led to ownership arising from adverse possession if the dispute is between private parties, the application judge found that publicly owned land of this kind is immune to claims for adverse possession.

The application judge reviewed the history of public ownership of the Disputed Land. In 1958, the City Lands, which include the Disputed Land, were expropriated by the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (the “Conservation Authority”) as part of a larger stretch of land bordering the Humber River. The application judge found that the City Lands were “taken for public use” and that “‘expropriation’ by its very nature is an action for public purposes.”

The application judge found that, in 1971, these City Lands were conveyed by the Conservation Authority to the City for a nominal sum of $2.00. One of the components of the City Lands, the public laneway, allowed access for the residents' rear-facing garages. The application judge reviewed the record with respect to the Disputed Land after the conveyance and concluded, at para. 54:

[54] Until this application seeking an adverse possession claim, there was no evidence that the City was aware of the lands being public; nor that any city funds have been expended to maintain the disputed lands. It stands to reason that this was, in part, because the applicants' predecessors had fenced off and excluded the land from the public.

The application judge characterized the property owners' extended fencing of the parkland as a deprivation of a reasonable use of the Disputed Land by the public. The application judge found that the Disputed Land could be put to use for the public benefit. The Disputed Land is part of a public park, and the City has plans to turn it into an access point to Étienne Brûlé park and the 29-kilometre Humber River Recreational Trail. She found that for over 50 years, “the property owners encroached on public lands with fencing to exclude public use. By their actions, they significantly narrowed the very access area to the public park.”

The application judge concluded that public parkland is immune to claims for adverse possession. She found that “a private individual must not be able to acquire title by encroaching on public lands and fencing off portions for their private use in the manner of two private property owners”. The lands were originally required for a “very high public interest” — they were expropriated for a public purpose and conveyed to the City as parkland. If allowed, the application judge reasoned, this would set a “dangerous precedent”.

Analysis #

The sole issue on this appeal is whether the application judge erred in finding that the appellants could not succeed in their claim for adverse possession over the Disputed Land. To resolve this issue, I must consider two questions: first, whether the application judge applied the proper adverse possession analysis to the facts of this case; second, whether the Real Property Limitations Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. L.15 ("RPLA") affects this analysis, and specifically whether, as the appellants argue, the operation of the RPLA supersedes the common law and governs this dispute.

(1) The Common Law Scheme for Adverse Possession Claims #

In Nelson (City) v. Mowatt 2017 SCC 8, [2017] 1 S.C.R. 138, at para. 17, Brown J. describes the common law basis for adverse possession as follows:

Adverse possession is a long-standing common law device by which the right of the prior possessor of land, typically the holder of registered title and therefore sometimes referred to as the “true owner”, may be displaced by a trespasser whose possession of the land goes unchallenged for a prescribed period of time. From as early as The Limitation Act, 1623 (Eng.), 21 Jas. 1, c. 16, the prior possessor’s right to recover possession was curtailed by limitation periods.

Adverse possession at common law is established where the claimant had (i) actual, open, notorious, constant, continuous and peaceful possession of the subject land for the statutory period of 10 years; (ii) an intention to exclude the true owner from possession; and (iii) effective exclusion of the true owner for the entire 10-year statutory period: Billimoria v. Mistry 2022 ONCA 276, 470 D.L.R. (4th) 406, at para. 27, citing Vivekanandan v. Terzian 2020 ONCA 110, 443 D.L.R. (4th) 678, at para. 21.

Canadian courts have treated adverse possession in the context of public lands at common law as distinct. In part, this is because the common law rationales for adverse possession between two private parties do not apply to publicly owned property.

Scholars have posited three rationales at common law for adverse possession between private parties. First, the doctrine of adverse possession penalizes landowners who “sleep on their rights” and rewards the “working possessor” — the “reward-penalty” explanation. Second, based on similar reasoning, the doctrine encourages land to be put to its best, or most productive, use. Third, the doctrine encourages property owners to monitor their property and resolve any boundary, title, or other disputes, expeditiously, and in doing so, “protects the settled expectations of an adverse possessor who has acted on the assumption that her occupation will not be disturbed”: see Bruce Ziff, Principles of Property Law, 6th ed. (Toronto: Carswell, 2014), at pp. 141-45. See also Jeffrey E. Stake, “The Uneasy Case for Adverse Possession” (2001) 89 Geo L.J. 2419. None of these rationales have application against a municipal parkland.

First, a municipal authority which allocates land-use according to statute cannot be said to “sleep on its rights” in relation to land designated as parkland, or for conservation or as an open space.

Second, adverse possession cannot be said to result in better uses of land than those pursued by public authorities. As reflected in municipal zoning laws, there is an important public interest in the allocation of land for different uses, including land for transportation and industry, land for residential development and land for parkland, conservation or open spaces.

Third, it is not realistic to expect a municipality to monitor the entirety of its land for signs of encroachment. As the application judge in this case observed, at para. 74, “The City is simply unable to patrol all its lands against such adverse possessors. The courts cannot demand the same vigilance of a private landowner to watch its borders of a public entity.” Further, where private parties object to the municipal zoning of particular land for particular uses, there are statutory dispute resolution processes which must be followed. Therefore, the rationale of encouraging monitoring and settling disputes also has little if any application in the context of adverse possession of municipal parkland.

Indeed, it is difficult to identify any rationale for adverse possession against municipal parkland. However, save where adverse possession of public lands has been barred by statute, the common law has developed analytical approaches that leave open, at least in some circumstances, that adverse possession against such property remains possible.

In his chapter on “Capacity to Hold and Deal with Interests in Land” in Anne Warner La Forest, Anger & Honsberger Law of Real Property, 3rd ed. (Toronto: Carswell, 2006), at §24:10, G. Thomas Johnson summarizes this principle as follows:

Municipalities, cities and towns have the power to acquire property by dedication, by devise, and by prescription. A town council which is authorized to expropriate land for specified purposes cannot exercise that power for different purposes. Where legislation has prescribed the mode of acquiring property, any other mode of acquisition is excluded. For example, the power to acquire land for a housing project does not permit a council to acquire shares in the corporation which owns the necessary land.

The right of ownership in real property held by a city or town for the common benefit or use of its inhabitants or of the Queen’s subjects in general (i.e., a highway) is of such a public character that it cannot, as a general rule, be lost by adverse possession over the prescriptive period. [Footnotes omitted; emphasis added.]

In Hughes v. Fredericton (City) 216 N.B.R. (2d) 387, at para. 10, aff’d 225 N.B.R. (2d) 264 (C.A.), the court cited the emphasized passage above with approval. The court accepted, at para. 12, that at common law, municipal land zoned as parkland is held in trust for the public, and generally not available for adverse possession:

I find that the entire portion of the land acquired by the City of Fredericton was zoned for parkland and there was a clear intention that it was acquired for public use. It would be difficult, if not impossible, for a claimant to acquire such land by adverse possession. As soon as the land was zoned for parkland for public use, it was held in trust by the City for the public. [Emphasis added.]

The Development of the Public Benefit Test in the Common Law of Adverse Possession in Relation to Public Lands #

Faced with the fact-specific analysis of adverse possession in the context of municipal land, where it is generally not available for adverse possession but where no complete bar or immunity is applicable, courts have developed a “public benefit” test to determine whether the municipal land at issue is immune from adverse possession.

In Hackett v. Colchester South (Twp.), [1928] S.C.R. 255, Duff J. stated in obiter remarks he was “much impressed” by the proposition that lands dedicated to public use and duly accepted by a municipality give rise to rights of enjoyment by the general public. He characterized these rights as “closely analogous to the rights of the public in respect of a public highway”, and the title of the municipality in such lands should not be capable of being nullified by claims of adverse possession: at p. 256.

In light of Colchester, subsequent decisions rejected adverse possession claims against municipal lands, reasoning that it is inconsistent with the “high public interest purpose” to which those lands were or could be put: Woychyshyn v. Ottawa (City) 2009 88 R.P.R. (4th) 155 (Ont. S.C.), at para. 13, and Prescott & Russell (United Counties) v. Waugh 2004 15 M.P.L.R. (4th) 314 (Ont. S.C.).

In Prescott & Russell, Charbonneau J. found that municipal land that had been acquired for public forestry purposes could not be lost by adverse possession any more than the rest of the forest into which that land had been incorporated. Charbonneau J. held, at para. 21:

When a municipality acquires lands for forestry purposes a very high public interest purpose arises as can be seen by the meaning the legislature has ascribed to that expression. It makes eminent sense that, in order to protect this vital public interest and as a matter of public policy, lands held by a municipality in such circumstances cannot be the subject of a claim for adverse possession.

In Woychyshyn, at para. 13, Ray J. dismissed a claim for possessory title to municipal parkland registered to the City of Ottawa, reasoning that there is a high public interest in maintaining such lands:

I have serious doubts that municipally owned land can be subject to a claim for possessory title. The Respondent’s evidence included a description of the complex procedures and processes required before municipal property can be disposed of. It suggests there is a high public interest in the preservation of municipal property. It should not be disposed of easily. A loss of property through adverse possession would be contrary to this high public interest.

In Oro-Medonte (Township) v. Warkentin, 2013 ONSC 1416, Howden J. found that a lakeshore promenade owned by the Township, but used and maintained in part by owners of lake-front lots, was immune from adverse possession. In reaching this conclusion, Howden J. summarized these earlier precedents and proposed the following test, at para. 119:

[L]ands held by a municipality other than as public road allowances which meet the following factors are immune from claims of neighbouring landowners based on prescriptive rights or adverse possession:

(i) the land was purchased by or dedicated to the municipality for the use or benefit of the public, or as here, for the use or benefit of an entire subdivision as well as the public at large; and

(ii) since its acquisition by the municipality, the land has been used by and of benefit to the public.

Howden J. set out the rationale underlying the “public benefit” test. He stated that land acquired by a municipality and used for public purposes should be understood as being held in trust for the benefit of the public, and therefore title over such land cannot be lost or extinguished by reason of ordinary acts or omissions associated with adverse possession. Howden J. found legislative support for this approach in the elaborate processes designated by statute governing when and how municipalities can sell or convey municipal property. He concluded that, given such property is owned by municipality by way of quality title for the public benefit, fairness and justice require that no two people should be able to deprive the public of that benefit.

The approach developed in Warkentin to the “public benefit” test subsequently was adopted in Richard v. Niagara Falls 2018 ONSC 7389 (Ont. S.C.J.), 4 R.P.R. (6th) 238, aff’d on other grounds, 2019 ONCA 531. In that case, a claim for adverse possession of municipal land was not made out because the applicants failed to prove that their use of the land was inconsistent with the city’s intended use. Henderson J., after citing Warkentin, stated in obiter, at para. 27:

[I]n order to be immune from such a claim for adverse possession, the municipality must show that the land was purchased or dedicated for the use of the public, and that the land has been used by and of benefit to the public. [Emphasis added.]

In Richard, Henderson J. incorporated the “public benefit” test into the third factor of the test for adverse possession (i.e., whether the city was effectively excluded from possession). I note that this was an incorrect placement of the “public benefit” test, which is instead a limitation to some claims for adverse possession for public lands. However, I summarize here the approach taken in Richard to clarify the proper characterization of the common law test. In Richard, the court focused on the de facto situation, which in that case was that the city intended to allow the public to make use of the trail in question. While the court referred to the de facto use by the city, as opposed to whether the city had formally designated the disputed land as a park, Henderson J.’s formulation of the test introduces the possibility that if a claimant can otherwise meet the threshold for adverse possession — and there is no evidence the disputed municipal land is actually in use for the public — an adverse possession claim could succeed. For the reasons elaborated below, I would not accept this characterization of the common law test.

As the appellants point out, some adverse possession claims against municipalities involving parkland have succeeded. For example, in Teis v. Ancaster (Town), (1997), 35 O.R. (3d) 216 (C.A.), this court dismissed an appeal from a decision granting adverse possession to private landowners over a strip of land and laneway in a public park. The appeal was decided on the common law test of mutual mistake since neither the private landowners nor the municipality had argued different rules applied to the common law of adverse possession in this factual setting. Nonetheless, Laskin J.A., in obiter comments, expressed “some discomfort” over applying the ordinary rules of adverse possession to municipal parkland, at pp. 228-229:

Most adverse possession claims involve disputes between private property owners. In this case, the Teises claim adverse possession of municipally owned land. I have some discomfort in upholding a possessory title to land that the Town would otherwise use to extend its public park for the benefit of its residents. Still, the Town did not suggest that municipally owned park land cannot be extinguished by adverse possession or even that different, more stringent requirements must be met when the land in dispute is owned by a municipality and would be used for a public park. This case was argued before the trial judge and in this court on the footing that the ordinary principles of adverse possession law applied. The application of those principles to the evidence and the trial judge’s findings of fact justify extinguishing the Town’s title to the ploughed strip and the laneway.

[…]

Whether, short of statutory reform, the protection against adverse possession afforded to municipal streets and highways should be extended to municipal land used for public parks, I leave to a case where the parties squarely raise the issue. [Emphasis added.]

In my view, Teis stands for the proposition that it is open to a municipality to waive its presumptive title over parkland. While in Teis this was done through agreement that the “ordinary” rules of adverse possession applied, this waiver may also be accomplished by acknowledging a private landowner’s adverse possession and consenting to a transfer of title (as was done with the neighbour’s property in this case), or simply by a municipality acquiescing to adverse possession, where it has clear knowledge of its parkland property being adversely possessed by private landowners, and agreeing to take no steps to interfere with that adverse possession.

Aside from those exceptional circumstances, the general rule that municipal parkland is not available for adverse possession has been given expression through the development of the “public benefit” test as set out above.

The appellants argued before the application judge that the Disputed Land does not meet the public benefit standard because it clearly was not in public use over the relevant time period (as it had been fenced off by the previous owners of the property). The application judge accepted this position.

On appeal, however, the appellants now argue that the “public benefit” test has not been endorsed by an appellate court and should be rejected entirely as inconsistent with the RPLA. For the reasons set out below, I do not accept this position.

For its part, the City argues that the “public benefit” test is good law, but that the application judge was incorrect in finding its threshold was not met in this case. The City contends that the Disputed Land was expropriated for public use and private landowners should not be able to defeat that use by fencing off public land for private benefit. According to the City, as held by the application judge, municipal parkland of this kind should be treated as immune from adverse possession.

I see the proper approach to adverse possession of municipal parkland lying between the two positions of the parties in this appeal. Under this approach, while municipal parkland is generally unavailable for adverse possession, it may become available exceptionally where the municipality has waived its presumptive rights over the property either expressly or by acknowledging or acquiescing to a private landowner’s adverse possession of parkland.

The Application of the Common Law of Adverse Possession to the Facts of this Case #

Applying the “public benefit” test to the record before her, the application judge concluded that, “The City was unable to provide evidence that the land was used by the public sometime in the 13 years after acquisition, before it was fenced out. I find it thereby fails the Public Benefit Test.”

As elaborated above, the application judge nonetheless held that it would be inappropriate to permit a claim in adverse possession to succeed in circumstances where public lands are fenced off by private individuals, as this would set “a dangerous precedent.”

In my view, the application judge treated as two separate considerations what should be seen as a single question to be addressed by the court in applying the public benefit analysis. Where land is acquired by a municipality and zoned as parkland or a space to be accessible to the public, such land should be treated as presumptively in use for the public benefit unless there is evidence the municipality has acknowledged and acquiesced to its private use. It is not enough to show that the land was rendered in fact unavailable to the public by the actions of private landowners.

Therefore, in this case, it was not necessary that the City demonstrate the disputed land actually was used specifically for a public benefit during the period prior to it being fenced off (i.e., between 1958 and 1971). Rather, the sole question to be addressed was whether the appellants, in seeking title through adverse possession, could displace this presumption of public benefit to this municipally owned land zoned to be used as parkland — for example, by showing that, while the Disputed Land was acquired for a public benefit, the municipality, with full knowledge, acknowledged or acquiesced to its use for the benefit of the then-owners of the appellants' property.

On this point, it is helpful to consider the City’s aforementioned consent, in 2013, to an order in favour of the easterly neighbours of the appellants, declaring those neighbours the successful adverse possessor of a rectangular portion of the City Lands abutting the informal laneway. The application judge referred to this consent as undertaken in a “cavalier” manner. The City indicated in oral submissions that this consent may simply have been an error, based on the mistaken belief that this parcel had been zoned residential when the land fell under the Borough of York. No such consent or acknowledgment by the City, however, has been made in relation to the Disputed Lands at issue in this appeal. Nor can it be said, in light of the application judge’s factual findings, that the City acquiesced to the use of the Disputed Land by the appellants or previous owners of this property during the period prior to it being fenced in or afterwards. The evidence was to the contrary, as there is nothing in the record to indicate that the City was aware the fenced off Disputed Land was municipal parkland. By contrast, the appellants were aware that the fenced off land was municipal property and not part of their title, which is why they sought to purchase the property from the City.

Generally, if a claimant acknowledges the right of the true owner, then possession will not be adverse. “Acknowledgment of title will thus stop the clock from running”: McClatchie v. Rideau Lakes (Township) 2015 ONCA 233, 53 R.P.R. (5th) 169, at para. 12, citing Teis, at p. 221, and see also 1043 Bloor Inc. v. 1714104 Ontario Inc. 2013 ONCA 91, 114 O.R. (3d) 241, at para. 73. In this case, however, the relevant time period was not when the appellants sought to purchase the Disputed Land, but rather when the previous owners first fenced it off.

Another way of looking at the question is whether the municipal parkland was intended to be, and would have been used for the public benefit, but for interference of the private landowners. Where, as here, this is the case, the party bringing a claim for adverse possession against a municipality will not have met the test to show the land has not been used for a public benefit.

I take this formulation to be consistent with the view expressed by the application judge in finding that, “the private landowner may not proceed to fence off public lands and exclude the public and succeed in a claim for adverse possession.” To the extent such a scenario would not meet the “public benefit” test as set out in Warkentin and Richard, the test was framed too narrowly in those cases.

Therefore, I would reframe the test for adverse possession of public land developed in cases such as Warkentin and Richard adopted by the application judge, as follows: adverse possession claims which are otherwise made out against municipal land will not succeed where the land was purchased by or dedicated to the municipality for the use or benefit of the public, and the municipality has not waived its presumptive rights over the property, or acknowledged or acquiesced to its use by a private landowner or landowners.

Based on this reframed test, I conclude the application judge came to the correct result by finding adverse possession at common law was unavailable against the municipal parkland in this case.

(2) The Statutory Scheme for Adverse Possession Claims #

The appellants argue that the application judge’s decision deprives them of the protection afforded by ss. 4 and 15 of the RPLA and therefore should be rejected.

Section 4 of the RPLA reads:

4. No person shall make an entry or distress, or bring an action to recover any land or rent, but within ten years next after the time at which the right to make such entry or distress, or to bring such action, first accrued to some person through whom the person making or bringing it claims, or if the right did not accrue to any person through whom that person claims, then within ten years next after the time at which the right to make such entry or distress, or to bring such action, first accrued to the person making or bringing it.

Courts have interpreted s. 4 of the RPLA as clarifying that adverse possession, where established at common law, will give rise to a limitation period of 10 years, after which the party engaging in adverse possession will gain rights over the land.

Section 15 of the RPLA reads:

15. At the determination of the period limited by this Act to any person for making an entry or distress or bringing any action, the right and title of such person to the land or rent, for the recovery whereof such entry, distress or action, respectively, might have been made or brought within such period, is extinguished.

Therefore, where an adverse possessor of land maintains possession of the requisite character for a period of 10 years, s. 4 of the RPLA bars the remedies of the paper title holder with respect to that land and s. 15 of the RPLA extinguishes the “true owner’s” title to that land: see Teis, at para. 8.

Section 16 of the RPLA contains an exception to the application of these provisions in favour of certain categories of public land, including public highways, and waste or vacant land of the Crown:

16. Nothing in sections 1 to 15 applies to any waste or vacant land of the Crown, whether surveyed or not, nor to lands included in any road allowance heretofore or hereafter surveyed and laid out or to any lands reserved or set apart or laid out as a public highway where the freehold in any such road allowance or highway is vested in the Crown or in a municipal corporation, commission or other public body, but nothing in this section shall be deemed to affect or prejudice any right, title or interest acquired by any person before the 13th day of June, 1922.

It is common ground among the parties that the exception in s. 16 establishing immunity from adverse possession for certain kinds of public land does not extend to municipal parkland such as the Disputed Land. The application judge did not refer to this provision, or to the RPLA at all in her reasons. Although the RPLA was referred to in the materials in the proceeding below, the legislative scheme was not the focus of either party’s submissions.

[…]

While s. 16 of the RPLA, first enacted in 1922, codified one aspect of this common law rule with respect to certain exemptions from the operation of ss. 4 and 15, in my view, nothing in the RPLA suggests it was intended to preclude the further development of the common law in public lands not of the kind categorized in that provision.

[Justice Sossin concluded that the RPLA did not act as a “complete code” to bar application of the common law of adverse possession.]

For these reasons, I would dismiss the appeal.

Brown J.A. (dissenting) – #

Parks are good things. Every morning I look out my window and enjoy the sight of the sun rising over the tree canopy of one of Toronto’s oldest and largest parks. When at work, I can look out my window and see the residents of a green-space-starved, concretized, downtown Toronto core enjoying the small, construction-free patch of grass that remains of Osgoode Hall’s West lawn. Adequate parks are vital to maintaining one’s sanity and socializing with one’s neighbours in an urban sea of steel and glass. Parks give rise to pleasant thoughts and strong sentiments.

That said, a case such as this which involves a claim by homeowners to adverse possession of a small patch of a municipally-owned greenspace that has formed their backyard for decades cannot be decided on the basis of sentiments about parkland. The appellants are entitled to have their case decided in accordance with the governing principles of law. Those principles are set out in statute, the Real Property Limitations Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. L.15 (the “RPLA").

The application judge did not apply those legal principles.

Instead, she stepped outside the governing statutory regime to consider whether the City of Toronto (the “City”) enjoyed the benefit of a recent, judge-made exception to the statutory scheme, the so-called “Public Benefit Test” asserted and articulated by the court in Oro-Medonte (Township) v. Warkentin, 2013 ONSC 1416, 30 R.P.R. (5th) 44. She concluded the City did not. So, the application judge went further. She created an even broader judge-made test that would immunize the Disputed Land from the appellants' matured adverse possession claim. The application judge articulated her test as follows: a “private landowner may not proceed to fence off public lands and exclude the public and succeed in a claim for adverse possession.” Hereafter I shall refer to the rule created by the application judge as the “Judicial Public Lands Immunity” rule. In my view, by ignoring the RPLA and creating a new judge-made rule, the application judge erred in law. She should have granted the appellants the relief they sought; they were entitled to it under the existing law.

My colleagues support the approach taken by the application judge, albeit they tweak her judge-made test a bit. I respectfully but very strongly disagree with my colleagues' decision and their analysis. I therefore dissent.

The Disputed Land is approximately 340m2 in size: a postage stamp when viewed in the context of the overall size of the adjacent Étienne Brûlé Park, which winds along the Humber River from the Old Mill to just south of Dundas Street West. But the land makes up most of the backyard used by the appellants.

Reasonable people can disagree as to whether, as a matter of public policy, municipal lands, including parkland, should be exposed to adverse possession claims regardless of the strength of the claim — here, there is no dispute the appellants have satisfied the statutory requirements to extinguish the City’s title to the Disputed Land — or the size of the lands affected. However, the appellants are entitled to have their claim decided not on the basis of what some judges might wish the law to be, but on the basis of what the law is.

Statute–the RPLA–sets out the requirements for establishing adverse possession in Ontario. Applying the law as it now is, the appellants succeed on their claim. There is no dispute about this fact. Yet, the application judge and my colleagues have denied the appellants' claim on the basis that courts are entitled to look beyond the law as it is and, instead, determine the claim based on the law as the courts think it ought to be. They have pushed the RPLA aside in order to create a legal rule, not found in the statute, about what type of land should be immune from claims for adverse possession. In my respectful view, their arrogation of such rule-making power constitutes legal error.

As I understand my colleagues' reasons, the key difference that separates our views is this: my colleagues take the view that common law principles continue to govern the law of adverse possession; by contrast, I read the history of that law as disclosing that a statutory codification and reformation of the law in the area took place almost two hundred years ago, a view that I think is supported by the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Nelson (City) v. Mowatt 2017 SCC 8, [2017] 1 S.C.R. 138, at para. 17.

As a result of those different views, my colleagues think it open to a judge to create new legal rules regarding adverse possession, including exempting lands from the operation of adverse possession, notwithstanding the narrow list of exempt lands set out in RPLA s. 16: waste or vacant Crown land, and road allowances and highways on Crown and municipal land. On my part, I think the RPLA acts as a comprehensive code of the principles of adverse possession subject, of course, to proper statutory interpretation. The courts certainly continue to possess the power to interpret and apply the provisions of the RPLA. Indeed, a large body of case law has developed around the interpretation of the statutory terms “possession” and “dispossession” that lie at the heart of the RPLA. However, I do not regard proper statutory interpretation as including a judicial power to amend the provisions of the RPLA, which I think is the “on-the-ground” result of the decisions of the application judge and my colleagues. Therein lies our fundamental difference. And, as I shall explain in what follows, therein lies the reason for my dissent.

I would allow the appeal, set aside the judgment, and grant the appellants the relief sought in their notice of application.

But first I must apologize to the reader for the length of this dissent. It turned out to be much longer than I had anticipated. In my defence, I think this appeal raises an issue of fundamental importance. Not whether the appellants are entitled to a declaration of possessory title over the Disputed Land–of course they are. Everyone acknowledges the appellants have met the statutory requirements for such a declaration. But while it is important that the appellants should receive their legal due, of greater importance is the way in which the courts in this case have denied the appellants their legal due. That judicial denial raises an issue that transcends the interests of the parties to this appeal.

Courts have become very powerful in this country. Yet, there is little that holds judges accountable for the exercise of their powers. The other branches of government–the legislatures and the executives–are accountable to the people for their decisions through various mechanisms, including the review of their conduct by the courts. By contrast, no one supervises the courts and the judges who populate them. (Whether that is a good thing or bad thing, I leave for others to debate in other forums.)

For the purposes of this case, the point I wish to make is this: for courts to play a lawful and legitimate role in a democracy, their lack of accountability mandates that judges exercise their powers with restraint and within proper bounds. In my view, and with all due respect to the application judge and my colleagues, that has not happened in this case.

[…]