Victoria (City) v Adams

2008 BCSC 1363 (CanLII)

Ross J. — #

I Introduction #

This litigation arises from what Senior District Judge Atkins in Pottinger v. Miami (City), 810 F. Supp. 1551 (U.S. Dist. Ct. S.D. Fla. 1992) at 1554 described as:

… an inevitable conflict between the need of homeless individuals to perform essential, life-sustaining acts in public and the responsibility of the government to maintain orderly, aesthetically pleasing public parks and streets.

The particular issue in this litigation concerns the prohibition against erecting temporary shelter on public property that is contained in the Parks Regulation Bylaw and the Streets and Traffic Bylaw (the “Bylaws”) of the City of Victoria (the “City”). Natalie Adams, Yann Chartier, Amber Overall, Alymanda Wawai, Conrad Fletcher, Sebastien Matte, Simon Ralph, Heather Turnquist and David Arthur Johnston (the “Defendants”), who are all homeless people living in the City, contend that this prohibition infringes the rights of homeless people to life, liberty and security of the person in a manner not in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice, contrary to s. 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, [Charter] being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, (U.K.), 1982, c. 11. The intervener, the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (the “BCCLA”), supports the defendants in this contention.

The intervener, the Attorney General for the Province of British Columbia ( the “AGBC”), and the City, contend that the claim does not fall within the scope of s. 7 of the Charter, that the prohibition does not infringe s. 7 and that in any event any infringement is justified pursuant to s. 1 of the Charter. The City contends that the prohibition is necessary to preserve and maintain the City’s parks.

The following findings were made on the basis of the evidence submitted at trial:

-

(a) There are at present more than 1,000 homeless people living in the City.

-

(b) The City has at present 104 shelter beds, expanding to 326 in extreme conditions. Thus hundreds of the homeless have no option but to sleep outside in the public spaces of the City.

-

(c) The Bylaws do not prohibit sleeping in public spaces. They do prohibit taking up a temporary abode. In practical terms this means that the City prohibits the homeless from erecting any form of overhead protection including, for example, a tent, a tarp strung up to create a shelter or a cardboard box, even on a temporary basis.

-

(d) The expert evidence establishes that exposure to the elements without adequate protection is associated with a number of significant risks to health including the risk of hypothermia, a potentially fatal condition.

-

(e) The expert evidence also establishes that some form of overhead protection is part of what is necessary for adequate protection from the elements.

On the basis of this evidentiary record and for the reasons that follow, I have found that a significant number of people in the City of Victoria have no choice but to sleep outside in the City’s parks or streets. The City’s Bylaws prohibit those homeless persons from erecting even the most rudimentary form of shelter to protect them from the elements. The prohibition on erecting shelter is in effect at all times, in all public places in the City. I have found further that the effect of the prohibition is to impose upon those homeless persons, who are among the most vulnerable and marginalized of the City’s residents, significant and potentially severe additional health risks. In addition, sleep and shelter are necessary preconditions to any kind of security, liberty or human flourishing. I have concluded that the prohibition on taking a temporary abode contained in the Bylaws and operational policy constitutes an interference with the life, liberty and security of the person of these homeless people. I have concluded that the prohibition is both arbitrary and overbroad and hence not consistent with the principles of fundamental justice. I finally have concluded further that infringement is not justified pursuant to s. 1 of the Charter.

II History of the Litigation #

This action was commenced by the City in October 2005 as an action to obtain a civil injunction to enforce municipal bylaws respecting parks and public space.

The City established and maintains a public park named Cridge Park. In October 2005, a tent city was established at Cridge Park (the “Tent City”) by a number of homeless people, including the named Defendants. A group of up to 70 people occupied the park, setting up more than 20 tents. Two large kitchen areas were constructed using tables and electrical cords that ran from the cooking area to an outdoor electrical outlet in the church building located adjacent to the north side of the park.

Relying on two City bylaws, the Parks Regulation Bylaw and the Streets and Traffic Bylaw, which at that time prohibited, inter alia, loitering or taking up temporary abode overnight in public parks, the City commenced enforcement proceedings under s. 274(1)(a) of the Community Charter, S.B.C. 2003, c. 26. To this end, it filed a writ seeking an injunction, inter alia, declaring the use and occupation of Cridge Park by the occupants of the Tent City to be in contravention of the Bylaws; restraining the Defendants and others from contravening the Bylaws; and authorizing and empowering the police to arrest those found contravening the Bylaws.

On October 14, 2005, a notice was distributed to the persons who were occupying the park. The notice stated:

NOTICE TO ILLEGAL OCCUPIERS OF CRIDGE PARK

We are the solicitors for the City of Victoria and advise you of impending injunction proceedings that have been authorized by Council with respect to this matter. This means that we will obtain a Court Order requiring you to remove yourself and your possessions off Cridge Park. In particular, we advise that persons who are presently loitering and/or camping at Cridge Park, and any other park within the City of Victoria, are in contravention of the City’s Parks Regulation Bylaw.

In particular, Section 28 of the Parks Regulation Bylaw No. 91-19 states that:

(1) No person may … loiter or take up a temporary abode overnight on any portion of any park, or obstruct the free use and enjoyment of any park by any other person, or violate any bylaw, rule, regulation or notice concerning any park.

(2) Any person conducting himself as aforesaid may be removed from a park and is deemed to be guilty of an infraction of this bylaw.

Accordingly, you are ordered to vacate Cridge Park immediately, and in any event no later than Monday, October 17, 2005 at 10:00 a.m. Failure to do so may result in the confiscation of your camping equipment and other personal property. It will further result in investigatory and injunction proceedings without further notice to you.

We further advise you that damage to trees, gardens and other City property will result in criminal and civil sanctions.

We urge you to avoid the loss of your possessions by moving to temporary housing operated by the Victoria [C]ool Aid Society at either one of the following two locations:

(1) Streetlink Emergency Shelter (co-ed)

1634 Store Street

ph: 383-1951

(2) Sandi Merriman House (adult woman)

809 Burdett Street

ph: 480-1408

Please use the above services if you are in any need of food and shelter.

Finally, be advised that you are not permitted to move yourself or your belongings to any other City park or public access way within the jurisdiction of the City of Victoria. Again, you risk the confiscation of your personal property.

Thank you in advance for your anticipated cooperation.

[emphasis in original]

The persons who were staying in the Tent City did not respond to the notice. The City then brought an application for an interlocutory injunction pursuant to s. 274 of the Community Charter. The City sought injunctive relief in the following terms:

(1) The defendants and anyone else having notice of this order be restrained from loitering or taking up a temporary abode overnight in any portion of lands legally described as, and commonly known as Cridge Park; …

(2) The defendants and anyone else having notice of this order be restrained from posting any advertisements or handbills of any kind in any portion of Cridge Park within the City of Victoria;

(3) The defendants and anyone else having notice of this order be restrained from erecting any tent or shelter in any portion of Cridge Park within the City of Victoria;

(4) The defendants and anyone else having notice of this order remove from Cridge Park within the City of Victoria any items, including, but not limited to, signs, chattels, tents, tarps, swings, personal belongings of any type and other thing which in any way encumbers or obstructs the free use and enjoyment of any portion of Cridge Park or has been otherwise placed in contravention of the bylaws, and in the event the defendants or anyone else having notice of this order fail to remove such obstruction or thing, that the plaintiff be at liberty to do so at the cost of the defendants or other person having notice of this order;

(5) Authorizes and empowers any peace officer to arrest and remove any person the peace officer has reasonable and probable grounds to believe is contravening or has contravened the provisions of any order issued by this honourable court.

[…]

III The Bylaws #

The City is authorized to regulate, prohibit and impose requirements in relation to public places pursuant to ss. 8(3) and 62 of the Community Charter, which provide:

Fundamental Powers

8(3) A council may, by bylaw, regulate, prohibit and impose requirements in relation to the following:

(a) municipal services;

(b) public places;

(c) trees;

(d) firecrackers, fireworks and explosives;

(e) bows and arrows, knives and other weapons not referred to in subsection (5);

(f) cemeteries, crematoriums, columbariums and mausoleums and the interment or other disposition of the dead;

(g) the health, safety or protection of persons or property in relation to matters referred to in section 63 [protection of persons and property];

(h) the protection and enhancement of the well-being of its community in relation to the matters referred to in section 64 [nuisances, disturbances and other objectionable situations];

(i) public health;

(j) protection of the natural environment;

(k) animals;

(l) buildings and other structures;

(m) the removal of soil and the deposit of soil or other material.

[…]

Public place powers

62 The authority under section 8(3)(b) [spheres of authority — public places] includes the authority in relation to persons, property, things and activities that are in, on or near public places.

The City has enacted Parks Regulation Bylaw No. 07-059. Under the provisions of this current Parks Regulation Bylaw, sleeping in parks or public spaces in no longer prohibited. The Bylaw does prohibit taking up a temporary abode. The Parks Regulation Bylaw provides in part:

Damage to environment, structures

13(1) A person must not do any of the following activities in a park:

(a) cut, break, injure, remove, climb, or in any way destroy or damage

(i) a tree, shrub, plant, turf, flower, or seed, or

(ii) a building or structure, including a fence, sign, seat, bench, or ornament of any kind;

(b) foul or pollute a fountain or natural body of water;

(c) paint, smear, or otherwise deface or mutilate a rock in a park;

(d) damage, deface or destroy a notice or sign that is lawfully posted;

(e) transport household, yard, or commercial waste into a park for the purpose of disposal;

(f) dispose of household, yard, or commercial waste in a park.

(2) A person may deposit waste, debris, offensive matter, or other substances, excluding household, yard, and commercial waste, in a park only if deposited into receptacles provided for that purpose.

Nuisances, obstructions

14(1) A person must not do any of the following activities in a park:

(a) behave in a disorderly or offensive manner;

(b) molest or injure another person;

(c) obstruct the free use and enjoyment of the park by another person;

(d) take up a temporary abode over night;

(e) paint advertisements;

(f) distribute handbills for commercial purposes;

(g) place posters;

(h) disturb, injure, or catch a bird, animal, or fish;

(i) throw or deposit injurious or offensive matter, or any matter that may cause a nuisance, into an enclosure used for keeping animals or birds;

(j) consume liquor, as defined in the Liquor Control and Licensing Act, except in compliance with a licence issued under the Liquor Control and Licensing Act.

(2) A person may do any of the following activities in a park only if that person has received prior express permission under section 5:

(a) encumber or obstruct a footpath;

[…]

Construction

16 (1) A person may erect or construct, or cause to be erected or constructed, a tent, building or structure, including a temporary structure such as a tent, in a park only as permitted under this Bylaw, or with the express prior permission of the Council, […]

Mike McCliggott, Acting City Manager, deposed that the City’s policy concerning the interpretation and application of the Parks Regulation Bylaw and the Streets and Traffic Bylaw as reflected in the operational policy of the Victoria Police is as follows:

(a) Parks Regulation Bylaw — when police encounter people sleeping in a park [during daytime hours] and there is no evidence of those persons taking up temporary abode in the park, they are not awoken or asked to move on;

(b) Streets and Traffic Bylaw — where police encounter homeless people sleeping in public spaces between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m., they do not generally awake or request the person(s) to move on if they are not obstructing a sidewalk, street or other right-of-way, or interfering with the use of a public amenity such as a bus shelter;

(c) In both cases, when concerned about a person’s welfare, police may need to waken the person in order to assess their health condition.

He deposed that the City does not prohibit people from creating shelter for themselves so long as a person is not taking up a temporary abode. People are allowed to protect themselves from the elements and to stay warm while they are sleeping through simple, individual, non-structural, weather repellent covers that are removed once the person is awake. He deposed that it is the City’s position that the Parks Regulation Bylaw prohibits the taking up of a temporary abode overnight and accordingly no tents, tarps that are attached to trees or otherwise erected, boxes or other structures are permitted.

The parties agreed to proceed on the basis that the current state of the law is reflected in the combination of the Bylaws and the operational policy described by Mr. McCliggott. The focus of the constitutional inquiry is directed to the gap between what is permitted by the Bylaws and operational policy of the City and what is prohibited by those Bylaws and the policy.

IV Facts #

A. The Homeless in Victoria #

1. The Number of Homeless in Victoria #

There have been several recent studies that have attempted to identify the number of homeless people in Victoria. All of the studies recognised the difficulties in conducting an accurate survey of this population such that all efforts to count are likely to result in underestimates. The most recent, thorough and comprehensive of these studies is the Mayor’s Task Force Report.

The Mayor’s Task Force Report, published on October 19, 2007, concluded that at least 1,200 people are homeless in or near downtown Victoria and another 300 are living in extremely unstable housing situations. The Gap Report of the Analysis Team’s included in the Mayor’s Task Force Report noted that the baseline statistics for determining homeless numbers in Victoria are likely an under-reporting and that current planning efforts to address the needs of the chronically homeless should be calculated based upon 1,500 individuals.

The Mayor’s Task Force Report concluded at p. 7 that “without the addition of sufficient supported housing units, the homeless population in Victoria is expected to increase by 20-30 percent per annum”, or an additional 300-450 people per year.

A survey of the homeless in Victoria was conducted on January 15, 2005, in which 150 community volunteers were assigned to survey specific geographical routes in the Greater Victoria area between the hours of midnight and 6:00 a.m. On that night the temperatures dropped to minus 10°C. The survey identified 700 homeless people. One hundred and sixty-eight people were found sleeping outside. The survey identified 47 children dependent upon someone who was homeless.

2. Profile of the Homeless Population #

The Homeless Needs Survey taken in 2007 and cited in the Mayor’s Task Force Report provided further information with respect to the composition of the homeless population in Greater Victoria.

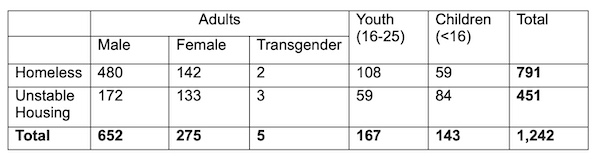

The Gap Analysis Report included the following results of that survey at p. 7:

Table 1: Homeless and unstably housed people identified through Homeless Needs Survey

As noted in this chart, that survey identified 791 persons who were homeless, as opposed to being unstably housed. Of those, 108 were youths between the ages of 16-25 and 59 were children under the age of 16. The surveyors, however, were of the view that this represents a significant underestimate and that the correct figure for homeless young people is likely between 250-300. The survey identified 74 homeless people who had children staying with them. Nineteen percent of those persons surveyed with children were homeless as opposed to being unstably housed.

The Mayor’s Task Force Report contained a Report of the Expert Panel. The Report of this group concluded at pp. 7-8:

-

Within the Capital Regional District, I,242+ residents are homeless, which incIudes residents of all ages, including children and seniors, with a peak age for men between 31 and 49

-

75 percent of homeless residents are male

-

Two-thirds of homeless residents are absolutely homeless

-

30 percent of homeless residents are high risk for health needs; 70 percent are low to moderate risk for health needs

-

Mental illness and substance use are the norm with at least 40 percent suffering from diagnosable mental illness

-

At least 50 percent of homeless residents are struggling with problematic substance use including alcohol, drugs that are injected (most commonly heroin and cocaine), and drugs that are smoked (including crack cocaine and crystal methamphetamines)

-

There are an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 injection drug users in Victoria, of whom at least 40 percent are homeless or unstably housed

-

The injection drug population is relatively young; 75 percent are male and 20 percent are Aboriginal

-

One survey found that 13 percent are infected with HIV and 74 percent are infected with Hepatitis C virus

-

Victoria has a problem with public injection; 30 percent of injection drug users report that the street is the place they most commonly inject drugs

-

25 percent of homeless residents have co-occurring disorders (mental illness and substance use problem)

3. Shelter Beds in Victoria #

The Report of the Gap Analysis Team described the number and distribution of shelter beds in Victoria at p. 15:

There are 141 permanent shelter beds in Victoria:

10 beds for youth

131 beds for adults

20 beds for women only

21 beds for men only

90 beds for both men and women

An additional 30 emergency youth mats are provided through the Out of the Rain Shelter during the colder months. When the Extreme Weather Protocol is activated, there are an additional five beds for women and 130 mats available across a number of locations. Of the 135 Extreme Weather spaces, 110 are located in Victoria and 25 are located in Saanich. At the height of extreme weather, 326 residents can be sheltered, leaving the remaining 1,200 plus homeless residents out in the rain.

It is clear that even including the Extreme Weather Protocol shelter spaces, the number of homeless people in Victoria substantially exceeds available shelter space. In addition, shelters have restrictions on the number of nights a person can stay and often bar those who are addicted to alcohol or drugs.

The City submits that in fact the number of shelter beds is sufficient to meet demand, at least during the time when the Extreme Weather Protocol is in effect. The City relied upon the rough draft of the 2007/08 Victoria Area Extreme Weather Protocol Final Report in support of this contention. [Note: the final draft of this Report was not in evidence.] The Report notes that the Extreme Weather Protocol was in effect on 81 nights during the period between November 21, 2007, and April 20, 2008. […]

VI Analysis #

[…]

A. Section 7 #

[…]

3. Does this Claim Follow Within the Scope of Section 7? #

[…]

(d) Is this Claim About Property Rights?

The AGBC and the City contend that the Defendants claim the right to camp on public property and that this makes the claim in essence about property rights. They submit further that property rights do not fall within the scope of s. 7, citing Alcoholism Foundation of Manitoba v. Winnipeg (City), [1988] 6 W.W.R. 440, 59 Man. R. (2d) 83 (Man. Q.B.), rev’d on other grounds (1990), 69 D.L.R. (4th) 697, 65 Man. R. (2d) 81 (Man. C.A.); Marshall Estate, Re, 2008 NSSC 93, 263 N.S.R. (2d) 347 (N.S. S.C.); and IBM Canada Ltd. v. R., 2001 FCT 1175, 212 F.T.R. 70 (Fed. T.D.), aff’d 2002 FCA 420, 298 N.R. 399 (Fed. C.A.). In their submission, the Defendants’ claim is tantamount to an appropriation of public property for private use.

In my view, this objection rests upon a mischaracterization of the matters at issue in this summary trial. The litigation had its origins in the Tent City erected in Cridge Park. It is also the case that many of the Defendants deposed that they wanted to be able to set up and maintain a camp in a park and that for a variety of reasons they preferred the camp in Cridge Park to accommodation in shelters. However, in this summary trial application, the relief sought by the Defendants is not what the AGBC and the City contend is the right to camp on public property. In other words, the issue of the right to camp in public spaces in the sense of a right to set up a semi-permanent camp, like the one established in Cridge Park, is not before the Court.

Rather, the issue is the prohibition on erecting even a temporary shelter taken down each morning in the form of a tent, tarp or cardboard box that is manifested in the current Bylaws and operational policy of the City. In my view, the issue before the Court on this summary trial application is not an assertion by the Defendants of a right to property as contended by the AGBC and the City.

In that regard, I agree with the submission of counsel for the Defendants that the AGBC and the City cannot and do not take issue with the proposition that homeless people must sleep, and, given the current situation in Victoria, that some of them must sleep on public property. The use of some public property by the homeless is unavoidable. Whether or not they are allowed to keep themselves dry with a simple tent or a cardboard box, as opposed to lying with a tarp on top of their faces, does not change the nature of that utilization of public space.

Related to this is the nature of the use of the property at issue. Unlike the distribution of public funds, the use of park space by an individual does not necessarily involve a deprivation of another person’s ability to utilize the same “resource”. If monies are spent to provide social assistance or the funding of a specific drug, they cannot be used elsewhere. If, on the other hand, a piece of park property is used for someone to sleep at night with shelter, this does not mean that it cannot be used by others for other recreational uses during the day. There is simply no evidence that there is any competition for the public “resource” which the homeless seek to utilize, or that the resource will not remain available to others if the homeless can utilize it.

The nature of the government interest in public property has most often been discussed in the context of freedom of expression. In that context, the Supreme Court of Canada has definitively rejected the idea that the government can determine the use of its property in the same manner as a private owner. Public properties are held for the benefit of the public, which includes the homeless. The government cannot prohibit certain activities on public property based on its ownership of that property if doing so involves a deprivation of the fundamental human right not to be deprived of the ability to protect one’s own bodily integrity: see Comité pour la République du Canada - Committee for the Commonwealth of Canada v. Canada, [1991] 1 S.C.R. 139 (S.C.C.); Jeremy Waldron, ”Homelessness and Community” (2000) 50 U.T.L.J. 371.

I conclude that the Defendants are not asserting a property right. They do not claim that the homeless can exclude anyone from any City property, or determine the use of any City property. They do not seek to have public property allocated to their exclusive use. What they are seeking does not amount to an appropriation of public property. They are simply saying that the City cannot manage its own property in a manner that interferes with their ability to keep themselves safe and warm.

(e) Is there a Risk of Harm?

The final submission of the AGBC and the City in relation to their contention that this case does not fall within the scope of s. 7 is that there is no evidence that the prohibition causes harm or the risk of harm.

The City submits that the evidence shows that some homeless people may prefer to live in “tent cities” rather than in shelters or rather than actively participating in efforts to find them housing. The City submits that therefore it is not established on the evidence that the City’s Bylaws have an adverse impact on the life, liberty and/or security of a person merely by limiting the nature of the abode that persons may construct in public places. As discussed earlier in these Reasons, it is the case that some of the Defendants deposed that they preferred the Tent City in Cridge Park to accommodation in shelters.

However, the fact remains that there are many more homeless people in Victoria than available shelter. It therefore does not really matter whether some homeless people prefer to sleep in shelters or not — there is not sufficient room for them in the shelters. Moreover, as noted earlier, many of the Defendants deposed that they have been turned away from shelters. This is consistent with the other evidence before the Court. I note further that the Mayor’s Task Force Report submitted into evidence by the City did not conclude that there are sufficient shelter spaces for all who wish to use them.

It is correct that it does not follow from the fact that there are insufficient shelter spaces to accommodate the homeless that the Bylaws create an adverse impact. In order to analyse this issue it is necessary to examine the expert evidence and its implications with respect to the limitations on shelter imposed by the Bylaws and the operational policy. With respect to the limitations on shelter, the City submits that the only item excluded from the minimum equipment that in Mr. Hogya’s opinion is required for necessary minimum protection, is string; the implication is that the equipment the City permits is sufficient to protect against the risks associated with exposure to the elements.

Mr. Hogya’s opinion is that in addition to ground insulation, the necessary minimum protection includes overhead protection in the form of either a tent or a bivy sack and tarp that is strung up to erect a tent-like protection. The size of the tarp-like protection necessary depends upon weather conditions, ranging from 2m × 3m in mild weather to 4m × 4m in stormy weather. In addition, Dr. Hwang referred to shelter in the form of a tent, tarpaulin or cardboard box.

The point of each alternative is that it is necessary to secure overhead protection. However, the Bylaw and the operational policy prohibit the erection of even temporary overhead protection in the form of tents, tarps strung up or cardboard boxes. I find that the difference between what is prohibited and what is permitted is not string, but overhead protection, and it is in my view clear on the evidence that overhead protection is required to provide protection from the risk of exposure.

[…]

I have found that a significant number of people in the City of Victoria have no choice but to sleep outside in the City’s parks or streets. The City’s Bylaws prohibit those homeless persons from erecting even the most rudimentary form of shelter to protect them from the elements. The prohibition on erecting shelter is in effect at all times, in all public places in the City. I have found further that the effect of the prohibition is to impose upon those homeless persons, who are among the most vulnerable and marginalized of the City’s residents, significant and potentially severe additional health risks. In addition, sleep and shelter are necessary preconditions to any kind of security, liberty or human flourishing. I have concluded that the prohibition on taking a temporary abode contained in the Bylaws and operational policy constitutes an interference with the life, liberty and security of the person of these homeless people. Finally, I have concluded that the prohibition is both arbitrary and overbroad and hence not consistent with the principles of fundamental justice.

[…]

VIII Disposition #

Accordingly, this Court declares that:

(a) Sections 13(1) and (2),14(1) and (2), and 16(1) of the Parks Regulation Bylaw No. 07-059 and ss. 73(1) and 74(1) of the Streets and Traffic Bylaw No. 92-84 violate s. 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in that they deprive homeless people of life, liberty and security of the person in a manner not in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice, and are not saved by s. 1 of the Charter.

(b) Sections 13(1) and (2),14(1) and (2), and 16(1) of the Parks Regulation Bylaw No. 07-059 and ss. 73(1) and 74(1) of the Streets and Traffic Bylaw No. 92-84 are of no force and effect insofar and only insofar as they apply to prevent homeless people from erecting temporary shelter.

[…]