This first lesson will introduce you to the course structure and syllabus and help you to get familiar with our problem-based learning model.

Malcolm Lightbody on Unsplash

Learning Objectives

Learning objectives are statements about the skills, knowledge and attitudes learners will acquire or develop when they complete this lesson.

By the end of this week, you should be able to:

- Explain course procedures and expectations. After reading the Course Syllabus closely, you should be able to explain to a classmate who missed this first week the key information they will need in order to navigate the course.

- Describe what it means to engage in a "problem-based" approach to studying law and follow the hypertext structure of the course materials to answer a problem. Consider how this approach, along with the linked structure of the reading materials, is designed to help you develop a more independent and critical analysis of the readings.

- Define what it means to "spot" legal issues from a set of facts and begin to apply this skill in the context of our weekly problem.

- Identify two core themes from the readings that we will return to throughout the course, (1) the "public/private" distinction in property law and (2) the significance of "possession".

Welcome to Property #

For first-year law students, “property” can be a kaleidoscopic subject: fragmentary, blinkered, disorienting. As one (among many) possible ways of mediating our relationships with and in respect of land and other “things” both corporeal and incorporeal, property law offers up a disorderly pattern of principles, rules and norms. It is full of contradictions, real and apparent. It presents a space of dispossession and disadvantage for some, prosperity and security for others.

There are likewise many ways to teach and learn about property, to try to make sense of and bring some order within the kaleidoscope. In this course, we will approach the subject from a historical perspective–one that puts the critical emphasis on the role of land-based relationships in Canada as the legal ground that determines so much about who benefits from our economic system and who does not.

This first week of the course introduces you to the method of problem-based learning used in the course and starts to develop some of the key questions and themes that we will explore throughout the year.

Read the Syllabus! #

Before you start to read the course materials, please familiarize yourself with the procedures and expectations for our course this year. Start by reading the Course Syllabus. This is the document you’ll refer back to throughout the year to understand course logistics, policies and resources.

Aim to come to class this week with a good understanding of:

-

How to access the course website and assigned materials;

-

Course procedures for communicating with me and arranging appointments outside of class meetings;

-

Goals and expectations for class preparation and participation in class meetings;

-

How you will be evaluated in the course; and

-

Your rights and responsibilities based on law school and university policies.

I will highlight some key points from these materials at the beginning of this week’s class meeting and will make time for your questions about the syllabus.

Problem-Based Learning #

You may have already noticed that this coursebook looks quite different from most of the other casebooks you are using in first year. One obvious feature is that it is fully digital and freely accessible online. But more importantly, the book is organized around a certain approach to studying legal topics called problem-based learning. All of your reading and our classroom meetings will be based on and motivated by problems–both hypothetical problems and those drawn from real-world events, or some mix of the two. These problems are designed to help you develop the skills to effectively identify relevant legal questions and to think critically and independently about the answers.

Factual problems (or “hypos”) have been a familiar way of testing students’ analytical and reasoning skills in law schools for a long time–especially on final exams. Problem-based learning is related but different, in the sense that we start with the problems rather than end with them: the problems motivate what materials we read, how we read them and how we connect ideas and themes to one another.

Practically speaking, this means that the way you prepare and review the weekly course materials will look different in this course than it does in many of your other 1L courses. Each week, you will start by reviewing the assigned Lesson and then move straight to the Problem for that week.

History, Doctrine and Hypertext #

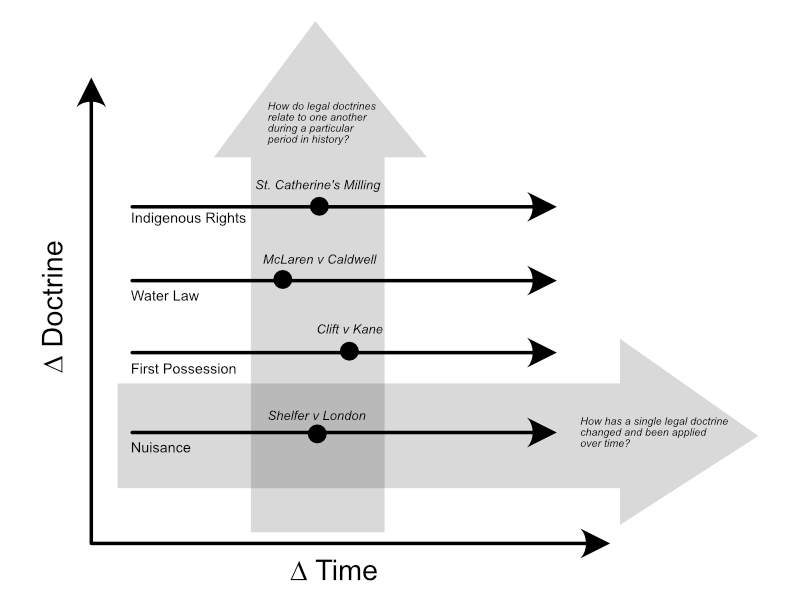

Most first-year law school courses are organized around the idea of legal “doctrines”, i.e. a set of legal principles addressing a particular legal issue and which evolve as cases are adjudicated and disputes resolved over time. This is a good way to study formal legal concepts but has its limitations for understanding law, legal change and legal pluralism in context. For example, we might learn about how the doctrine of “nuisance”–which governs land uses between neighbours–has emerged and been refined over the years to address a problem like industrial pollution. But studying nuisance in isolation makes it very difficult to understand how pollution and its underlying causes in resource development and economic production, in any given period, are affected by a whole range of different legal doctrines, from public land use controls to the law concerning wills and estates.

To address this challenge of “law in its historical context”, we need a way to study law in at least two dimensions at once: changes in doctrine over time and linkages across doctrines during certain periods of history. That is, as we study how nuisance law has changed over, say, the hundred years between 1900 and 2000, we also want to understand how nuisance law was connected to and influenced by other legal developments in and around, say, the mid-nineteenth or the mid-twentieth centuries.

If you are a visual learner, the following diagram might help you to understand this aim:

You might be thinking: this seems a bit complicated. So why do we want to do this? Well, because history matters. And it matters not just out of some academic interest in “the way things were” but because–if we want to make sense of our current legal context, as good lawyers must do–we need to build up a set of skills and practices that help us to critically interpret the past.

The biggest question, then, is: how? Rather than working only through a linear progression of doctrinal materials, as we would expect to do in a printed book, our coursebook is organized as a hypertext with a network of linkages that allow you to follow different pathways through the material. These pathways will trace single doctrines over time and multiple doctrines within a particular period.

Applying this framework means that you will be asked to make choices about how you approach and connect the assigned reading materials in light of the weekly problem you are trying to solve. This tests your capacity for independent critical analysis and asks that you to engage actively with the materials in a way that might feel unfamiliar at first but will most definitely pay off in the long run.

Weekly Problem: Protest at Dalhousie University

After you have read through the background for this week's lesson above, your next step is to review the weekly problem.

Students and local residents are engaged in a protest on the Quad and inside one of the administration buildings at Dalhousie. The University is considering a legal claim against the protesters as part of efforts to exclude their activities from campus.