This week we examine the role of private law tools to govern land uses in the face of a conflict between neighbors, including issues of the appropriate remedy in nuisance and the circumstances in which restrictive covenants run with title to the land.

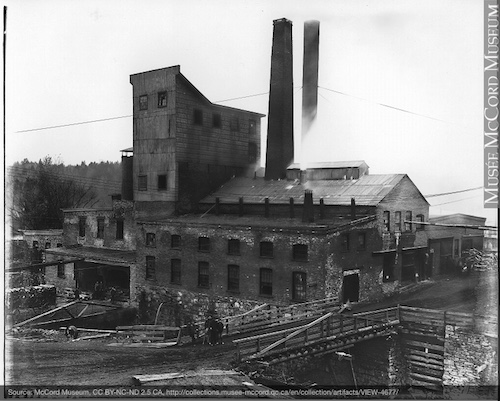

Canada Paper Company, Windsor Mills, QC, 1909 (Source, McCord Museum, Montreal).

Learning Objectives

Learning objectives are statements about the skills, knowledge and attitudes learners will acquire or develop when they complete this lesson.

By the end of this week, you should be able to:

- Discuss claims in nuisance and restrictive covenants as alternative means of governing property.

- Identify and describe the test for determining the appropriate remedy in nuisance, while critically assessing whether or not this test helps us to consistently resolve the contested legal issues that arise in nuisance cases.

- Explain how and in what form restrictive covenants came to be understood as "running with the land".

A Turn to Governance #

Over the past few weeks we have been focused on questions about recognizing relationships to land and about the central role of two concepts: possession and title. We now turn to a second group of topics that address how–once possession and title receive recognition in law–conflicting uses of land are governed as a matter of property.

From a historical perspective, as settler colonialism advanced based on law’s denial of Indigenous rights and sovereignty (our topic last week), post-Confederation nationalism sought to establish the economic foundation of this new country by continuing to pursue natural resource extraction and, increasingly, to advance industrialization. Central to this economic project were legal tools that developed to address the most significant “externalities” of these activities–namely, the inevitable land use conflicts arising from large-scale environmental pollution and from the growing concentration of people living in close proximity to one another, especially in burgeoning urban centres like Toronto, Montreal and Halifax. We will examine two of these important legal tools this week: (1) remedies available in the law of nuisance and (2) the rise of restrictive covenants annexed to land. While existing in different doctrinal areas, it is important to see both of these as key private-law technologies for regulating land uses in an era before the widespread application of public land use controls more familiar today.

Nuisance Law in an Industrializing Canada #

Widespread industrialization came somewhat late in Canada compared to England and the United States, where nuisance law was earlier addressed in the common law courts as a potential impediment to economic “progress”. As Jennifer Nedelsky explains:1

By the late nineteenth century, industrialization and urbanization were changing the shape of Canadian society: between 1880 and 1920 the population doubled from 3,689,257 to 8,788,483; 74.35 per cent of the population were classified as rural by the census of Canada in 1881; by 1921 the percentage had decreased to 50.48. Capital investment in manufactures increased from $165,302,632 in 1880 to $2,923,667,011 in 1920 and the gross value of all manufactured products from $469,847,886 in 1880 to $3,706,544,997 in 1920. Manufacturing, once diffused, was concentrating in industrial towns. Factories increasingly replaced small workshops, and steam-powered engines brought noise as well as productivity. As the nuisances of industrialization increased, so did the costs of eliminating them. Manufacturing establishments, for example, were becoming sufficiently large and important to local economies that ordering them to take their nuisances elsewhere would have had serious consequences.

Like their English and American counterparts before them, common law courts in Canada struggled to adjudicate nuisance claims in this evolving context, which often pitted the demands of business and the growing influence of industry against the traditional property rights of neighbouring landowners. However, because industrialization came relatively late to Canada, Canadian courts confronted nuisance cases against the background of legal principles already developed elsewhere. A key question became to what extent Canadian courts would follow these established precedents-—primarily from England-—or chart their own path.

Traditionally, the common law afforded heavy priority to the absolute protection of private owners rights to use and enjoy their property, enforced by way of an injunction against the offending activities of neighbouring landowners. In the Shelfer case you will read this week, the Court opened the door for greater flexibility on the part of courts to substitute an award of damages in place of a permanent injunction in appropriate circumstances. Legal historians have largely interpreted this move as an attempt by the Court to take a more accommodating position toward industrial interests.

Restrictive Covenants as “Private” Land Use Planning #

Nuisance offers one means to address conflicting land uses between owners after those conflicts arise. An alternative–and potentially more proactive–approach is for owners to form an agreement ahead of time about what which uses will be permitted, prohibited or required. This latter approach is represented by the law on restrictive covenants. Such covenants were initially viewed by the courts as simply contractual agreements between neighboring landowners that could only be enforced against original parties to the contract. With the precedent in Tulk and Moxhay, which you will read this week, certain of these contracts were transformed into a set of durable restraints on the proprietary freedom of owners. Restrictive covenants thereafter would become a crucial way for private owners to engage with one another in processes of land use planning and control–for example, to establish and sustain the “character” of their neighborhoods against the advance of urban pollution from heavy industry. Understanding how restrictive covenants came to be enforced (“run with the land”) and the legal requirements needed for them to be regarded as valid provides a helpful window onto the question of how recognized entitlements of property become subject to various forms of governance.

-

Nedelsky, Jennifer. “Judicial Conservatism in an Age of Innovation: Comparative Perspectives on Canadian Nuisance Law.” In Essays in the History of Canadian Law, edited by David H Flaherty, 281-322. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981, 284-5. ↩︎

Weekly Problem: GMOs

After you have read through the background for this week's lesson above, your next step is to review the weekly problem.

This hypo concerns a heritage corn grower's attempts to prevent pollination of their crops from GMO varieties grown by a neighbouring farmer.