Two claims for recognition of "Aboriginal Title" in New Brunswick under section 35 of the Constitution Act have been launched in recent years. This problem explores how these territories came to be understood in Canadian law as subject to both the Crown's radical title and to the common law estates of private parties.

Statement of Claim, 30 November 2021, Wolastoqey Nation v New Brunswick

Facts #

In recent years, two separate original Statements of Claim have been filed by Wolastoqey and Mi’gmaq Nations asserting title–under the Anglo-Canadian doctrine of “Aboriginal Title”–to large, overlapping territories in New Brunswick. Based on an initial review of key excerpts from those two claims, this week’s problem asks you to analyze the historical contributions of Canadian law to the current reality of settler colonialism that both cases attempt to confront.

The Wolastoqey Title Claim #

The plaintiffs in this claim are the Wolastoqey Nation at Matawaskiye (Madawaska Maliseet First Nation), Wolastoqey Nation at Neqotkuk (Tobique First Nation), Wolastoqey Nation at Pilick (Kingsclear First Nation), Wolastoqey Nation at Sitansisk (Saint Mary’s First Nation), Wolastoqey Nation at Welamukotuk (Oromocto First Nation) and Wolastoqey Nation at Wotstak (Woodstock First Nation), on behalf of all members of Wolastoqey Nation. The plaintiffs seek a declaration from the court that the Wolastoqey Nation has Aboriginal Title to lands in the claim area as well as damages and compensation from the Crown for breaches of the Crown’s fiduciary obligations, and for the unlawful occupation, appropriation, removal of resources from, and infringement of, the plaintiffs’ Aboriginal Title over their Traditional Lands, including infringements arising from the parties being in occupation of the Traditional Lands without permission from the plaintiffs.

According to the Statement of Claim:

The Plaintiffs are the First Nations residing in what is now New Brunswick that are part of the larger Wolastoqey Nation, which before the assertion of British sovereignty occupied vast tracts of territory, including territory in what are now New Brunswick, Québec and Maine.

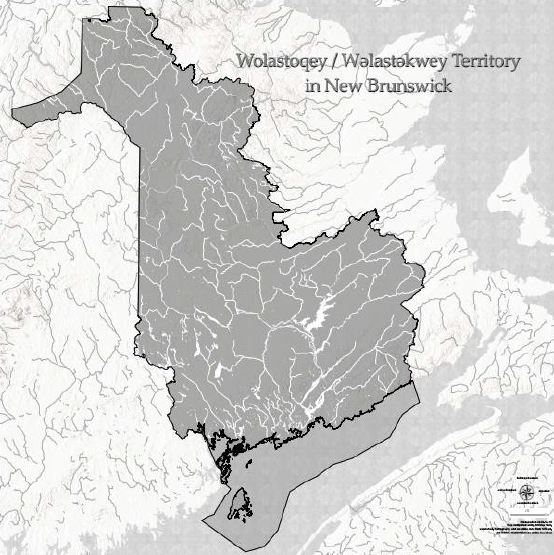

The territory occupied included the Traditional Lands, being what is now known as the Wolastoq, also known as the St. John River, watershed and surrounding area, including the land, subsurface land and minerals, airspace, land covered by water, offshore and inshore water bodies, foreshore, rivers, lakes and streams situated within this area. The Plaintiffs only seek remedies in this litigation with respect to their Traditional Lands within New Brunswick, and not with respect to their Traditional Lands found within the present boundaries of the Province of Québec and the State of Maine. A map of the Traditional Lands within New Brunswick is included in Schedule “A”.

The First Nations and members of the Wolastoqey Nation are the direct descendants of the Wolastoqey Nation which was present on the Traditional Lands prior to the British assertion of sovereignty.

Wolastoqey custom provided that members of each local group had use of its own local territory, including all of its lands, waters, and resources. However, Wolastoqey Nation as a whole had exclusive occupation of the entire Traditional Lands, and members of Wolastoqey Nation were able to travel and harvest freely throughout the Traditional Lands.

At the time of the British assertion of sovereignty in 1759, Wolastoqey Nation controlled, regularly used, exclusively occupied, and exercised exclusive stewardship and jurisdiction over their territory, including the Traditional Lands, in accordance with Wolastoqey law. Such law provided that a person from outside their territory was expected to seek permission to be present. Anyone seeking to pass through Wolastoqey Nation’s territory or to otherwise use the Traditional Lands would require such permission. It was customary that permission, if requested, would often be granted to other friendly Indigenous persons to travel through or to temporarily stay in the territory and to hunt, fish and gather to feed themselves while doing so.

Permission was also granted to certain French groups to occupy certain lands within Wolastoqey Nation’s territory. The Wolastoqey Nation generally had a friendly and allied relationship with the French and their presence in Wolastoqey Nation’s Traditional Lands helped to facilitate alliance, trade, and related activities.

Prior to and at the assertion of British sovereignty and continuing to present day, Wolastoqey Nation has used their Traditional Lands for a variety of purposes including hunting, fishing, gathering and other resource-harvesting activities, trade, and cultural and spiritual practices.

At all relevant times, from the assertion of sovereignty in 1758-1759, to the Peace and Friendship Treaties between the British and Wolastoqey Nation from 1725 to 1778, the British Crown recognized Wolastoqey Nation as the Indigenous people who exclusively occupied their territory, including the Traditional Lands.

From 1725/1726 to 1778, Wolastoqey Nation negotiated and entered into Treaties with the Crown, known as the Peace and Friendship Treaties. These Treaties do not provide for the surrender of lands to the Crown.

In entering into the Peace and Friendship Treaties, Wolastoqey Nation did not cede or surrender their Aboriginal title to the Traditional Lands.

Wolastoqey Nation’s title to the Traditional Lands has never been extinguished through surrender or legislation, and survives today.

[…]

The Defendants have infringed upon or otherwise breached the Defendants’ constitutional duties in respect of Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title in the Traditional Lands by alienating lands and undertaking, authorizing and/or permitting resource extraction and land use activities throughout the Traditional Lands without the Wolastoqey Nation’s consent.

Such uses and alienations of land were in breach of the Defendants’ duties to respect and protect Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title and have unjustifiably infringed Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title.

In particular, the Crown Defendants breached their duties to respect and protect Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title by actions including, but not limited to:

(a) issuing, replacing and renewing licences, leases, permits, authorizations, grants and other tenures to third parties or otherwise occupying, managing and allocating lands and resources in a manner which interferes with Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title;

(b) conveying land to themselves and to third parties without regard to Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title;

(c) passing laws which purport to enable or authorize Canada and New Brunswick to alienate lands and resources to third parties or to use those resources for their own benefit;

(d) purporting to exercise management, ownership and control over lands and resources without regard to Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title;

(e) committing or authorizing nuisances, trespass or other interferences which restrict or interfere with Wolastoqey Nation’s Aboriginal title;

(f) deriving royalties and other benefits from the lands and resources and denying Wolastoqey Nation the right to receive benefits therefrom;

(g) failing to protect and sustainably manage the lands and resources; and

(h) failing to adequately consult and/or accommodate Wolastoqey Nation or otherwise discharge the Crown’s fiduciary duties and/or the honour of the Crown in respect of the above activities.

The Statement of Claim further makes clear that the “Plaintiffs seek no relief as against fee simple holders not named as Defendants who hold fee simple in the Traditional Lands (‘Strangers to the Claim’)[i.e., most private titleholders]. The incidents of fee simple title enjoyed by Strangers to the Claim, including the incident of peaceable possession, are not placed in issue by the Plaintiffs. As outlined in paragraph 1(c), however, the Plaintiffs seek damages and compensation from the Province and Canada for the breach of Aboriginal title in the granting of fees simple in the Traditional Lands to Strangers to the Claim.”

In the fall of 2024, the Government of New Brunswick posted this “Minister’s message” on its website addressing the Wolastoqey claim. With a subsequent change in provincial government the message was removed from the website.

The Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn Inc. (MTI) Title Claim #

The plaintiffs in this claim are eight of the nine Chiefs of the Mi’gmaq First Nations in New Brunswick. Similar to the Wolastoqey claim, the MTI plaintiffs seek, among other remedies, a declaration of Aboriginal Title to lands in the claim area and an award of damages and compensation from the Crown.

According to the Statement of Claim:

Mi’gma’gi is a geographic territory composed of seven districts, which include what is today known as Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, the Gaspé Peninsula and parts of Quebec, parts of Newfoundland and Labrador, part of Maine and the Islands in the Baie des Chaleurs, as well as their surrounding coastal and marine areas. Mi’gma’gi includes not only these land areas, but also the waters, islands, air and resources of and around them.

[…]

The Mi’gmaq Nation, has occupied and cared for the lands and waters of Mi‘gma’gi since time immemorial.

Prior to, and at the time of European contact and the assertion of British sovereignty, Mi’gma’gi was, and continues to be, occupied and possessed communally by the Mi’gmaq Nation. Mi’gma’gi is the homeland of the Mi’gmaq, and at all material times the connection of the Mi’gmaq to Mi’gma’gi has been of central significance to and the source of the distinctive culture of the Mi’gmaq.

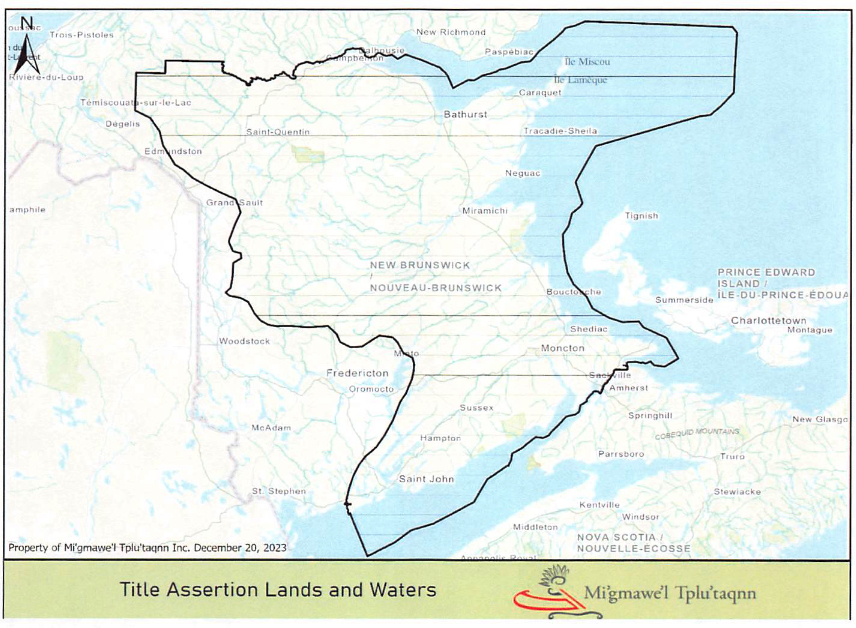

The Plaintiffs only seek remedies in this litigation with respect to the portion of Mi’gma’gi currently referred to as New Brunswick, including the land, subsurface land and minerals, airspace, land covered by water, offshore and inshore water bodies, foreshore, rivers, lakes and streams situation within this area. A map of the Title Area within New Brunswick is included in Schedule “A”. The Plaintiffs reserve the right to claim Mi’gmaq Title in respect of the whole or any portions of Mi’gma’gi in the future.

Prior to, and at the time of European contact and the assertion of British sovereignty, Mi’gma’gi was, and continues to be, occupied and possessed communally by the Mi’gmaq Nation. Mi’gma’gi is the homeland of the Mi’gmaq, and at all material times the connection of the Mi’gmaq to Mi’gma’gi has been of central significance to and the source of the distinctive culture of the Mi’gmaq.

The Plaintiffs only seek remedies in this litigation with respect to the portion of Mi’gma’gi currently referred to as New Brunswick, including the land, subsurface land and minerals, airspace, land covered by water, offshore and inshore water bodies, foreshore, rivers, lakes and streams situation within this area. A map of the Title Area within New Brunswick is included in Schedule “A”. The Plaintiffs reserve the right to claim Mi’gmaq Title in respect of the whole or any portions of Mi’gma’gi in the future.

Prior to and at the assertion of British sovereignty, the Mi’gmaq had a sophisticated system of governance which provided for decision-making at the Nation, District, and local or watershed level. Under this system of governance, Mi’gmaq people in each District and local area had use of that District, including all of its lands, waters, and resources. However, the Mi’gmaq as a whole had occupation of all of Mi’gma’gi (including the entire Title Area), and members were able to travel and harvest throughout Mi’gma’gi (including the Title Area), subject only to such restrictions as were imposed by local or district Chiefs and heads of families.

Prior to and at the assertion of British Sovereignty, the Mi’gmaq were a part of a larger Confederacy of Nations, known as the Wabanaki Confederacy, which included the Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati Nations. From time to time, the members of the Wabanaki Confederacy used each other’s territory, pursuant to Wampum agreements, protocols and understandings between these Nations.

Prior to and at the assertion of British sovereignty, the Mi’gmaq had a sophisticated system of governance which provided for decision-making at the Nation, District, and local or watershed level. Under this system of governance, Mi’gmaq people in each District and local area had use of that District, including all of its lands, waters, and resources. However, the Mi’gmaq as a whole had occupation of all of Mi’gma’gi (including the entire Title Area), and members were able to travel and harvest throughout Mi’gma’gi (including the Title Area), subject only to such restrictions as were imposed by local or district Chiefs and heads of families.

Prior to and at the assertion of British sovereignty, the Mi’gmaq continuously hunted, fished, and harvested in their territory and have used, cared for, and occupied the natural resources and all components on the natural resources therein. They have obtained their livelihood and subsistence from their territory and the natural resources thereof, and have continuously possessed, controlled and managed, and to the extent possible still possess, control and manage, the natural resources of their territory within the Title Area.

Prior to and at the assertion of British sovereignty, the Mi’gmaq enjoyed a special relationship with the land, waters and resources of what is now known as the Province of New Brunswick. The relationship of the Mi’gmaq with the land, water and all natural resources within the Title Area is the foundation upon which the Plaintiffs, and their ancestors, interact and govern their communities, and is an expression of Mi’gmaq law.

Prior to and at the assertion of British sovereignty, the Mi’gmaq exercised jurisdiction over the Title Area pursuant to Mi’gmaq legal and political regimes governing the use and occupation of land, and continues to do so today.

At all relevant times, from the assertion of British sovereignty to the Peace and Friendship Treaties between the British and the Mi’gmaq from 1725 to I779 the British Crown recognized Mi’gmaq ownership and jurisdiction over the lands and waters of Mi’gma’gi, including the Title Area.

[…]

Canada and New Brunswick and their predecessors had and have a duty to respect and protect Mi’gmaq Title.

The Defendants have infringed upon or otherwise breached their Constitutional Duties in respect of Mi’gmaq Title in the Title Area by alienating lands and undertaking, authorizing and/or permitting resource extraction and land use activities throughout the Title Area without the consent of the Mi’gmaq Nation.

Such uses and alienations of land were in breach of the Defendants’ duties to respect and protect Mi’gmaq Title and have unjustifiably infringed Mi’gmaq Title.

The Statement of Claim specifically states that “In respect of fee simple lands that are not held by the Crown, the Plaintiffs seek no relief against fee simple holders who hold fee simple title in the Title area (“Fee Simple Holders”). The incidents of fee simple title enjoyed by Fee Simple Holders, including the incident of peaceful possession, are not placed in issue by the Plaintiffs. As outlined in paragraph l(h), however, the Plaintiffs seek damages and compensation on behalf of the Mi’gmaq Nation from the Defendants, jointly and severally, for the infringement of Mi’gmaq Title in the granting of fees simple in the Title Area to Fee Simple Holders.”

The Statement of Claim goes on to say that “the Plaintiffs do seek a declaration on behalf of the Mi’gmaq Nation in respect of fee simple and industrial freehold lands that Mi’gmaq Title burdens the Crown’s allodial title.”

The Problem #

How did British and Canadian law prior to the 20th century establish the legal foundation for state-sponsored dispossession of Indigenous peoples as part of what has been described as a “cultural logic of elimination”?1 In what ways do the remedies being pursued by the parties in the Wolastoqey and MTI claims address this history of settler colonialism? In what ways do they not?

Analyzing the Problem #

Our problem this week takes a different form compared to those we have studied so far this term. Rather than provide you with a stylized set of facts (a “hypo”), the problem draws on real-world legal materials. More importantly, rather than have you “spot” issues and provide a legal analysis based on the facts and law, the problem asks you to develop a historical and normative analysis that demonstrates your engagement with a core theme–property and colonialism–we are exploring throughout the course (i.e. an “essay-style” answer).

One of the motivations for presenting you with this type of problem at this point in the course is that the contemporary doctrine of Aboriginal Title has changed radically since the late 19th-century. It would not help you much in your understanding of that contemporary doctrine to apply the legal framework developed more than a century ago directly to a set of recent facts. Nevertheless, because some of the core assumptions from this earlier period still pervade law today, it is crucial for you to have a clear understanding of its evolution over time. We will return to the contemporary legal framework for Aboriginal Title later in the course.

-

Patrick Wolfe, Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event (London; New York: Cassell, 1999), 4-5. ↩︎

Readings for this Week

Choose one of the reading materials from the list below--ordered alphabetically--to start analyzing this week's problem. At the end of your reading path you should have covered each of the materials on the list.

- A Brief Overview of Feudal Land Tenure: An excerpt that provides some brief background to the history of feudal land tenure and its relationship to common law estates as interests in land distinguished from ownership of the land itself.

- Constitution Act, 1982, Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, s 35: The key provision in Canada's constitution recognizing and affirming Aboriginal and treaty rights, including Aboriginal Title.

- Royal Proclamation (1763): A edict issued by King George III in 1763 following the Treaty of Paris--by which Britain acquired control over French territories in North America--and establishing the British Crown's colonial policy at the time with respect to Indigenous land rights.

- St. Catherine's Milling and Lumber Co. v R, (1886), 10 OR 196 (HC); [1887] 13 SCR 577; [1888] UKPC 70 (JCPC): A dispute between the governments of Ontario and Canada about title to land subject to Treaty 3 between the Anishinaabe and the Dominion government. The provincial government argued that title in the land had transferred to the Crown in right of Ontario at Confederation, while Canada asserted that Anishinaabe title to the land survived Confederation but was surrendered to Crown in right of Canada when Treaty 3 was signed.